The Empowerment Equation: Women, Work, and Pakistan’s Development

By Maryam Awais (Pakistan)

From sewing machines in small towns to motorcycles in major cities, women across Pakistan are quietly reshaping the nation’s economy. Their success isn’t just inspiring—it’s essential.

In a quiet neighborhood of Muridke, near Lahore, the gentle sound of a sewing machine hums through the afternoon heat. Shahnaz, a mother of three, sits cross-legged on the floor, carefully stitching a school uniform. A few years ago, she didn’t own this sewing machine. In fact, she didn’t earn any money at all. Like many women in Pakistan, Shahnaz stayed home, looked after her family, and relied on her husband for every rupee.

But things changed when she received a small loan of fifty thousand rupees from a local women’s support program. With it, she bought a stitching machine and started taking small orders from neighbors. Her work quickly gained attention, and within a year, she took a second loan and hired another woman to help her. Now, she runs a small but steady home business and earns enough to support her children’s school fees, food, and other expenses. “It gave me respect,” she says. “Not just outside, but inside my home too.”

Shahnaz’s story is not unusual. Across Pakistan, countless women are finding ways to break free from the barriers that once held them back. Some are learning new skills, others are starting businesses, and many are finding the courage to step outside the house and enter a workforce that has been missing their voices for too long.

Pakistan has one of the lowest rates of female labor force participation in South Asia. According to the World Bank, only about 23% of women are part of the workforce, compared to 78% of men. And even when women do work, they often earn much less—on average, just 16% of what men earn. Many of them work informally, from their homes, without contracts, protections, or recognition. These are not just numbers; they reflect a system where women are kept out of opportunities, not because they lack talent or ambition, but because of cultural barriers, lack of education, limited access to transport, and poor support from financial institutions.

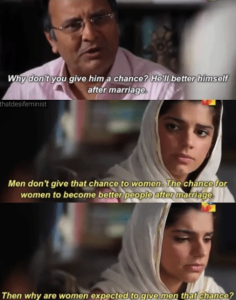

In many conservative households, especially in rural areas, women are expected to remain within the domestic sphere. Cultural beliefs often equate a woman’s honor with her physical presence in the home, discouraging work outside.

Religious misinterpretations also play a role. While Islam itself does not prohibit women from working—the Prophet Muhammad’s wife, Khadijah, was a successful businesswoman—local traditions often enforce patriarchal interpretations that restrict female mobility. Public harassment, lack of safe transportation, and male-dominated workplaces further deter women from seeking jobs. Moreover, over 62% of women in Pakistan do not have a bank account, and many lack property or legal documents required to access credit.

But things are slowly beginning to change. In Karachi, for example, a group of women are now working as electricians—something unheard of just a few years ago. Through a program called “Roshni Baji,” women like Nazia Seher have been trained to install wiring, fix electrical issues, and teach others about safety. Many of their clients are women who feel more comfortable letting a female electrician into their homes. “It’s not just about fixing wires,” says Nazia. “It’s about showing girls in our area that we can do this too.”

In Lahore, another group of women is taking on the streets—on two wheels. The Women on Wheels (WOW) program teaches women how to ride motorcycles, giving them the freedom to travel without depending on a male relative. Ghania, a college student, says learning to ride changed her life. “Before, I used to miss classes if my brother was busy. Now I can go anywhere. I feel free.”

In Lahore, another group of women is taking on the streets—on two wheels. The Women on Wheels (WOW) program teaches women how to ride motorcycles, giving them the freedom to travel without depending on a male relative. Ghania, a college student, says learning to ride changed her life. “Before, I used to miss classes if my brother was busy. Now I can go anywhere. I feel free.”

Access to credit and finance is another major challenge for women. Many don’t have bank accounts, national ID cards, or property in their name to use as collateral. But microfinance institutions like the Kashf Foundation are stepping in to fill this gap. Since its start in 1996, Kashf has given out over $496 million in small loans—most of them to women. These loans help women start small businesses—like beauty salons, tailoring shops, or catering services—and slowly build financial independence.

In the northern areas of Pakistan, in places like Skardu, women are now running shops and livestock businesses thanks to local programs that offer training and credit. One such program, the Hawa Project, found that when women earn money, they spend it on their children’s education, better food, and health. This not only helps individual families but lifts entire communities.

All these stories may seem different—a tailor in Punjab, a biker in Lahore, an electrician in Karachi—but they all point to one thing: when women are given a chance, they change lives. Not just their own, but the lives of everyone around them.

Women’s economic participation in Pakistan is being pushed forward by a mix of powerful forces—from grassroots activism to education, media, technology, and legal reform. Each of these plays a crucial role in breaking down the cultural and structural barriers that have long held women back.

Civil society organizations have led the charge. Groups like the Home-Based Women Workers Federation (HBWWF), Aurat Foundation, Shirkat Gah, and others have been instrumental in advocating for legal recognition and workplace protections for women. The passage of the 2018 Sindh Home-Based Workers Act, for example, was a landmark victory that came after years of organizing by women workers and rights activists.

Education is another major driver. More girls are entering school than ever before, and digital learning platforms are expanding access. Initiatives like CodeGirls Karachi and DigiSkills are teaching young women in-demand skills such as coding, freelancing, and digital marketing. These programs open doors to remote work, which is particularly valuable in conservative communities where women may not be allowed to work outside the home.

Education is another major driver. More girls are entering school than ever before, and digital learning platforms are expanding access. Initiatives like CodeGirls Karachi and DigiSkills are teaching young women in-demand skills such as coding, freelancing, and digital marketing. These programs open doors to remote work, which is particularly valuable in conservative communities where women may not be allowed to work outside the home.

Media and popular culture are also shifting public perception. Television dramas like Udaari and Zindagi Gulzar Hai have portrayed strong, working female characters, challenging traditional stereotypes.

Technology is giving women new ways to earn and serve. Startups like Sehat Kahani allow female doctors to consult patients via telemedicine, letting them work from home while providing care in underserved areas. E-commerce and freelancing platforms are also creating income opportunities for women who previously had no access to the formal job market.

Legal reforms and government programs are beginning to lay a stronger foundation. The Ehsas Kafaat Program, for instance, provides digital wallets to over seven million women, helping them gain financial independence. Programs like the Punjab Skills Development Fund are offering free vocational training in trades like tailoring, beauty, and hospitality.

Global examples are influencing change too. Countries like the UAE have shown that women can lead in business, politics, and science without compromising religious or cultural values. They are proving that religion and women’s empowerment are not mutually exclusive. The UAE now has 50% female participation in its Federal National Council, and women occupy key positions in science, space, and diplomacy. Their government actively promotes women in STEM and entrepreneurship, and this inclusivity has helped attract foreign investors and accelerate economic growth. Their progress is pushing Pakistan to reconsider old assumptions and invest more seriously in women’s inclusion.

Rwanda, a post-conflict country, has 63.8% women in parliament—the highest in the world. Bangladesh, Pakistan’s neighbor, has outpaced it in female labor force participation through investments in textile jobs, girls’ education, and social protection. These examples offer powerful lessons: when women are included, nations prosper—not just economically, but socially and politically.

Together, these elements—rights activism, education, media, tech access, policy reforms, and international inspiration—are steadily creating new possibilities for Pakistani women. The road is still long, but the direction is finally changing.

Research shows that when women earn money, they reinvest up to 90% of it into their families. Children stay in school longer. Nutrition improves. Health gets better. Domestic violence goes down. And the entire economy benefits. According to the World Bank, if Pakistan increases female labor force participation to match that of men, it could increase its GDP by more than 30%.

The future of Pakistan depends on this. We cannot develop as a nation while half of our population remains on the sidelines. Women’s economic empowerment is not just a women’s issue—it is a national issue. It is about fairness, yes, but it is also about smart economics.

To move forward, the government must make laws that protect and include informal workers. Banks need to make it easier for women to access loans. Schools should teach girls not just academics but life skills. Communities must support women’s freedom to work and move.

Cultural narratives around Islam and work must also be addressed directly. Scholars and religious leaders should publicly affirm that Islam supports women’s right to work, own property, and contribute to society—as demonstrated in other Muslim-majority countries. And all of us—whether in policy, business, media, or home—need to believe in the power of women.

Back in Muridke, as the sun sets, Shahnaz folds away her sewing machine and calls her children for dinner. Her hands are tired, but her eyes are full of pride. She has stitched more than just uniforms today—she has stitched a new path forward, one where women like her are seen, heard, and valued.

And if more women are given the tools and the trust, there’s no doubt: they’ll stitch the future of Pakistan. As Benazir Bhutto once said, “It’s not easy for women, no matter where they live. We still have to go the extra mile to prove that we are equal to men.”

That extra mile is being walked every day—through stitches, steps, and stories of resilience.

- World Bank. Labor force participation rate, female (% of female population ages 15+) – Pakistan.

- World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report.

- Global Findex Database 2021, World Bank.

- https://pchr.gov.ae/en/priority-details/gender-equality-and-women-s-empowerment#:~:text=Political%20Participation&text=Women%20also%20hold%2050%25%20of,ministerial%20positions%20held%20by%20women.

- IPU Parline, Monthly Ranking of Women in Parliament, https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking/#:~:text=The%20IPU%20publishes%20rankings%20of%20the%20percentage,on%20the%20basis%20of%20the%20ranking%20data.

- Clinton Global Initiative. Women and the Economy: The Smart Investment.

- World Bank. Pakistan@100: Shaping the Future.

About the Author: Maryam Awais holds a BA in Media Studies with a specialization in journalism. Passionate about advancing social justice and gender equality, she is dedicated to using her skills to make a positive impact. This fall, she will begin her MA in Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University. Currently, she is enhancing her understanding of women’s empowerment, human rights, and gender equality through programs like UN Women Training Centers and various online webinars. Eager to apply her knowledge in real-world settings, she is committed to creating meaningful change.

About the Author: Maryam Awais holds a BA in Media Studies with a specialization in journalism. Passionate about advancing social justice and gender equality, she is dedicated to using her skills to make a positive impact. This fall, she will begin her MA in Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University. Currently, she is enhancing her understanding of women’s empowerment, human rights, and gender equality through programs like UN Women Training Centers and various online webinars. Eager to apply her knowledge in real-world settings, she is committed to creating meaningful change.